Introduction

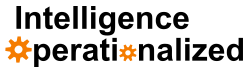

A recent attempt to improve the robustness of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) on image classification tasks has revealed an interesting link between robustness and interpretability. Models trained using adversarial training, a training procedure that augments training data with adversarial examples, have input gradients that qualitatively appear to be using more relevant regions of an input compared to models trained without adversarial training. The cover photo for this post shows this (middle row is without and bottom row is with adversarial training). This is an unexpected and welcome benefit of a regularization technique which has been shown to be the most effective defense against adversarial examples so far. Therefore in some cases, increasing model robustness improves model interpretability. You can see more examples on ImageNet and CIFAR10 in the original paper by Tsipras et al. However, this is only one side of the coin. While CNNs can outperform humans on some tasks/datasets, they are far from perfect since they suffer from low robustness to image corruptions such as uniform noise, and cannot generalize from one corruption to another. A naive solution to make CNNs robust to a set of corruptions is to augment the training data using these corruptions, but this has been shown to cause underfitting by Geirhos et al. Consider the three images below, and try to tell the difference between the middle and right image.

Noise visualization

Noise visualization

The salt and pepper noise image looks similar to the uniform noise image, yet augmenting training data only with salt and pepper noise has almost no effect on correctly classifying images corrupted with uniform noise. A possible explanation for this is that rather than learning to ignore noise like humans do, neural networks fit particular noise distributions and only become invariant to those they were trained on. This very important work by Geirhos et al. has sparked great interest in the research community to further understand the differences between human and computer vision. Perhaps by bridging this gap can improve both model interpretability and robustness. We’ll see if this is indeed the case later on, but we first describe one of the most fundamental differences in the features used by human vision for core object recognition, and computer vision for image classification.

Texture Bias

It has been observed by a follow up work by Geirhos et al., as well as work by Baker et al. that CNNs have a texture bias when making classifications. This means that an outline of a teapot filled in with the texture of a golf ball will be classified as a golf ball. If the goal is to identify various fabrics or materials in an image such as when summarizing the properties of clothing images, this behaviour is actually desired. However, for classification, it could lead to classifying an image of a car with an unusual paint job as grass for example. The fact that humans are biased towards using shape when making classifications is not merely an intuitive speculation, rather it is the result of thorough, controlled experiment. Participants were presented with so called cue-conflict images which were created by applying style transfer on ImageNet images so that they have a desired texture. However, the shape information is preserved. Such images look similar to the ones below taken from the work by Baker et al.

Cue conflict images from Baker et al. Click here for link to license

Cue conflict images from Baker et al. Click here for link to license

They were then asked to pick from a set of 16 classes for each image. Most of the time, the participants chose the class corresponding to the shape of the main object in the image, rather than the overlaid texture. The authors then proposed that perhaps encouraging models to have a similar behaviour bias to humans would have other added benefits of human vision such as corruption robustness. To achieve this preferred shape bias, they created a new dataset called Stylized ImageNet (SIN) which was obtained by applying AdaIn style transfer from a dataset of paintings to ImageNet. This causes texture to be an unreliable feature for classification since images of the same class will have random textures depending on the stylization used. SIN is a more difficult dataset to classify as shown by the fact that a model trained and evaluated on ImageNet achieves 92.9% accuracy, but when evaluated on SIN it only achieves 16.4% accuracy. Conversely, a model trained and evaluated on SIN achieves 79% accuracy, and when evaluated on ImageNet has 82.6% accuracy. A SIN-trained model has a shape-bias much more similar to that of humans, suggesting that the ability to classify stylized images is not achieved by remembering every style, rather by using shape. Even more important is the increased robustness to corruptions that was obtained by training on SIN. Except for two particular corruption types, robustness to all other considered corruptions was improved as a result of increased shape bias.

Adversarial Training

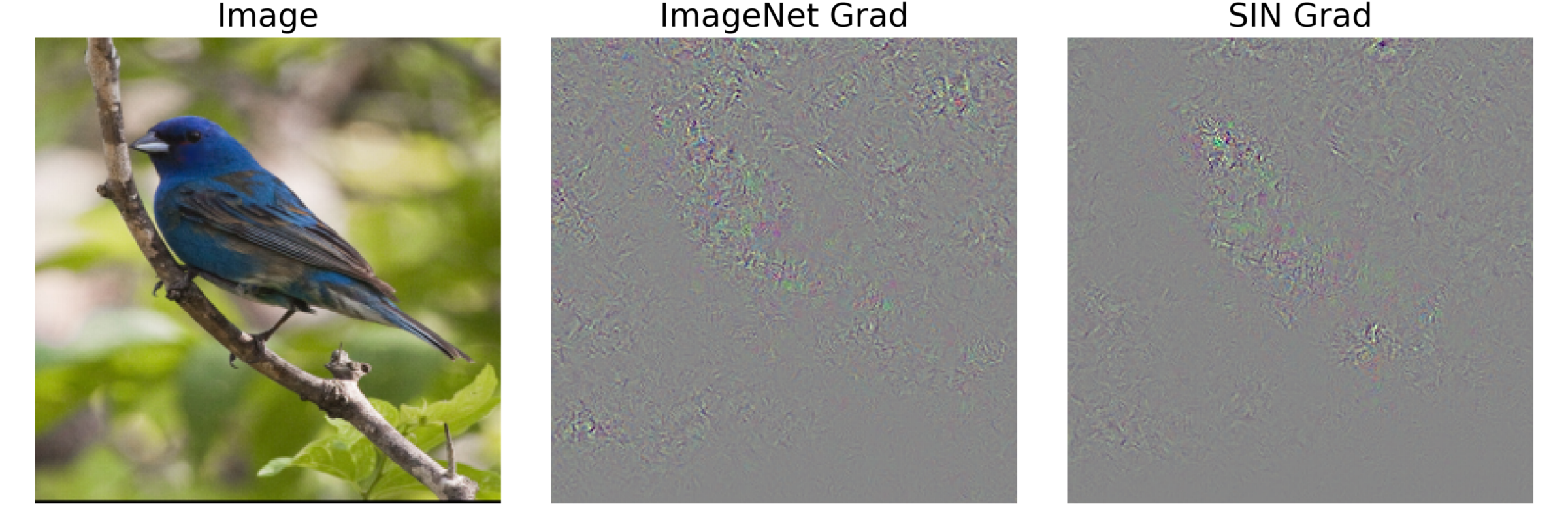

When adversarial training is used to explicitly make models robust against adversarial examples, the visualized gradients use features that are more aligned with human vision. Is this true for SIN-trained models? Do the gradient visualizations reflect the aforementioned shape bias? Fortunately these models are available online, so the heavy lifting has been done, and just the gradient visualization remains. As you can see below, there is a very slight difference between the gradients of a ResNet trained on ImageNet, and one trained on SIN, but nothing like what is obtained via adversarial training. This finding shows that the links between interpretability, corruption robustness, and behavioural biases are not yet understood. Moreover, the adversarial robustness of SIN-trained models has not been thoroughly characterized yet, though a simple FGS attack reveals no significant difference between ImageNet and SIN-trained models with the former having an accuracy of 12.1% and the latter 14.3% on a subset of 1000 ImageNet validation images.

So if gradient visualizations do not reveal a clear benefit of training on SIN, what else can be done to bridge the gap between human and computer vision? Perhaps mimicking behavioural biases that humans have is not sufficient. Additionally, human vision is multitask and can perform object tracking, segmentation, classification, etc. This reveals a possible issue with how vision models are currently being trained as silos for just one task of interest. If CNNs or other architectures are to exhibit the same properties we as humans take for granted, they will likely achieve this goal faster if trained in a multitask way leveraging several sources of supervision. Indeed, the limits of deep learning in domains such as language understanding have almost been reached as researchers realize that reasoning about the sizes and shapes of objects is very difficult when learning from text only. Combining multiple tasks together is a small but perhaps necessary step in addressing the most obvious differences between human and computer vision. However, there will likely be a long way to go even after this step considering how prevalent adversarial examples are even though researchers have been tying to defend against them for the past 6 years.